Tuned In: Meet Mastering Engineer Greg Calbi – New Jersey Monthly

“He walked in wearing a pair of small, Ben Franklin-type glasses and whipped out a leather-bound Jean-Paul Sartre philosophy book, which he read throughout the session,” Calbi recalls. “Once again, I realized that, for performers of all kinds, the persona and the real person are sometimes quite different.”

Calbi should know. In his long career, Calbi has mastered albums for a huge list of artists, including Bruce Springsteen, David Bowie, Bob Dylan, John Lennon, Paul Simon, the Beatles (rereleases), the Talking Heads, the Ramones, Blondie, Norah Jones, Branford Marsalis and Bon Iver, to name a few.

Granted, Calbi’s niche in the music ecosystem is neither high profile nor commonly understood. Mastering is the final polishing and preparation of recorded music before it is sent to streaming services or pressed into CDs or vinyl. In addition to checking that the songs on an album are in the correct format and order and have balanced levels and spacing between them, the mastering engineer subtly corrects any sonic deficiencies—such as harshness or lack of bass.

“A lot of times, the vocal levels may be either too loud or too low,” Calbi says. “That’s something that we check and can enhance. We can also run the overall sound through electronic hardware or plug-in software that can bring out some extra life in the instruments.”

[RELATED: Jersey’s Enduring Folk-Music Scene]

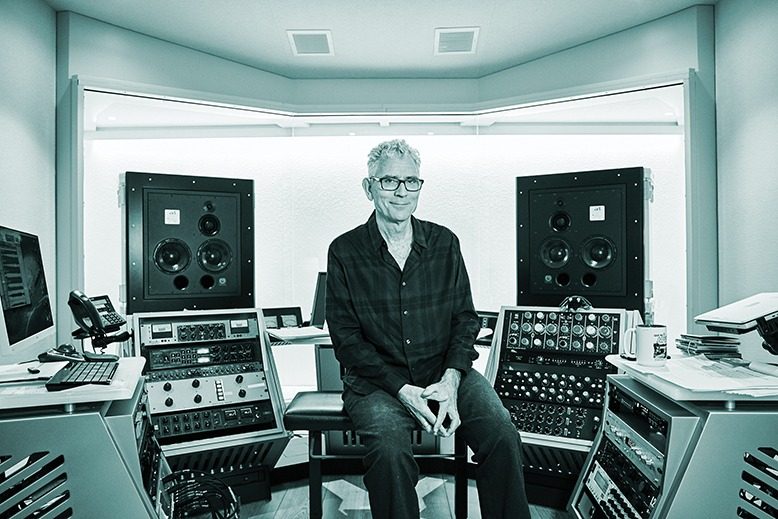

To be successful, mastering engineers require what’s referred to in the industry as golden ears—or hearing sensitive to the smallest sonic details. They also need specialized studios and expensive playback systems.

“Mastering is not something you do on the road,” Calbi says. “You master in a fixed environment between a set of speakers that, typically, you’ve had for many years.”

It also helps to be extremely familiar with your gear. “It’s the consistency of the sonic picture that we have that’s the advantage,” Calbi says. “Clients depend on the mastering person to enhance the music in a way that they couldn’t do in the recording studio.”

Calbi, 71, estimates that he’s mastered, on average, about five albums a week for 48 weeks a year throughout his 40-year career. That puts him “somewhere in the 7,500–8,000 album range.”

Calbi twisting the knobs in 1976. Courtesy of Greg Calbi

Calbi likes having artists attend his sessions. But not all mastering engineers do. “There are some people in my trade who actually forbid it, and some who just grudgingly go along with it. But I like to hang. I like the discussion of the music; I like the interplay.”

Some artists want to be there, some don’t. “I’ve done about 20 projects for Bob Dylan,” Calbi says, “but I’ve never met him. He always works through his manager.”

When Calbi mastered Springsteen’s Born to Run album in 1975, he worked at a studio inside the Record Plant—one of New York’s premier recording facilities—which is where Springsteen was recording the album.

“You’d see Bruce and say hello to him in the hallway,” Calbi says. And while Springsteen didn’t get into the minutiae of the mastering process, he was sharply focused on the results. “He’d listen to the record and evaluate how it sounded,” Calbi says. “Bruce was super involved in Born to Run, as he is in everything he does.”

Greg Calbi’s mastering projects have run the musical gamut. For Springsteen’s Born to Run, he says, “Bruce was super involved…in everything.”

When Calbi mastered Bowie’s classic 1975 album Young Americans, the artist made what could be described as a cameo appearance at the studio. “He had these two supermodels with him,” Calbi remembers. “They wanted to listen to the album. But probably by the third song, they got bored. They said, ‘Okay,’ and they left.”

For much of his career, Calbi has worked at Sterling Sound, a prestigious mastering studio, in which he became a partner 22 years ago. In 2018, Sterling Sound relocated from Manhattan to a converted old post office in Edgewater.

Moving from the city freed Sterling from the sky-high Manhattan rents, but there was some initial concern as to whether clients would travel to New Jersey to attend sessions. Those fears turned out to be unfounded.

“People love coming here,” Calbi says. “People from Brooklyn even love coming over, even though it’s kind of a schlep. They drive over. They’re happy to get out of the city. We have some interesting things right near us. We have a great Japanese market, a couple of really nice restaurants, a view of the river. It’s a nice little field trip for folks. We love being in Jersey.”

Although he worked in New York City for much of his career, Calbi has lived in Montclair since 1986. He and his wife, Dana, an artist and teacher, raised their two children in the Essex County township. Their son, Marlon, was the starting quarterback for the Montclair High School football team for three seasons and shortstop on the baseball team for four. Their daughter, Simone, developed an interest in international studies while attending Montclair High.

“I really love Montclair,” Calbi says. “I love the energy, and I love the type of person who wants to live here, who wants to put his butt on the line, pay the taxes, and be in a community of like-minded and active people, between the musicians and the artists and the writers and the journalists.”

Calbi doesn’t plan to retire from mastering anytime soon. He says business is still going strong—despite the sonic compromises inherent in streaming music, a depleted record industry and computer technology that makes DIY mastering possible (albeit with lower quality). “We still get a lot of people who want the service and who appreciate it,” he says.

Even the Covid-19 crisis has not impacted his workload, although it does prevent artists from attending his sessions. That takes away some of the fun for the gregarious Calbi. “I’ve just put in seven or eight straight weeks without a single client coming in,” he says. “It’s a different level of discipline when you’re working by yourself.”

Mike Levine leads a double life as a music journalist and musician. The former editor of Electronic Musician and Onstage magazines plays in three bands, produces and mixes music, and has composed for commercials and television shows.