Endless construction, rooftops, new arrivals: The Far West Side is booming – San Antonio Express-News

Slightly more than a year ago, just before her favorite president lost his reelection bid, Michelle Bruninga, a hair salon owner in Redondo Beach, Calif., lived in a top-floor condo with an endless view of the Pacific Ocean and walked the beach every day.

But she was not happy.

Bruninga, 50, was incensed over Black Lives Matter rallies in nearby Los Angeles, a Democratic governor she terms a “dictator,” pandemic-caused business problems and, as she puts it, “decriminalized criminals” on the streets.

With a teenage surfer son in tow, she came to San Antonio to visit a friend and had an epiphany.

“I remember seeing that big Cowboys Dancehall off I-35,” Bruninga recalled. “And there was this Trump rally with so many American flags. I saw people of every race. I felt I finally saw freedom. I got out of the car and just broke down.”

CENSUS TRACKER: See how your neighborhood, city and state changed in the last decade

On the day after Christmas, the two newly-minted Texans left California, drove 19 hours straight and became part of a remarkable demographic wave breaking over Texas’ major cities.

Bexar County grew by almost 300,000 people between 2010 and 2020, a 17 percent jump in population. They included 107,000 added to San Antonio, the nation’s seventh largest city, a nearly 8 percent increase, according to U.S. Census data.

Houston, Dallas, Austin, Fort Worth and Midland-Odessa all showed similar growth.

Unlike many newcomers, Bruninga had not done exhaustive online research on San Antonio’s neighborhoods and suburban communities. No careful weighing of school performance, home values, political leanings — she just drove around, checking out the vibe.

The median home price in Redondo Beach is $928,000. Bruninga wanted something more affordable, with uncluttered hills to remind her of an earlier California.

So she joined tens of thousands of others who skipped past neighborhoods north of Loop 1604 and gravitated to the Far West Side, where dozens of subdivisions have transformed the edge of the Hill Country with seemingly endless arrays of rooftops and new construction sites.

The new residents – first-time homeowners, newly middle class minorities, active and retired military, affluent professionals, absentee investors — aren’t all from out of town. But their arrival has made three contiguous census tracts the fastest-growing in Bexar County and a magnet for chain stores, strip malls, new schools and suffocating traffic.

Smiling young moms roll their double-strollers past clustered mailboxes and winding rows of $300,000-ish brick homes with thirsty lawns and wooden privacy fences. In some subdivisions there’s hardly a front porch anywhere and neighbors are so close they can almost reach out and borrow some cilantro.

The tracts cover a swath of land from the western edge of Government Canyon State Natural Area south to Culebra Road, sprawling out beyond Galm Road south to Talley Road and stopping just short of the massive Alamo Ranch development, an early anchor of the area’s growth.

As it nears the Medina County line, the humble, two-lane Culebra Road still physically resembles the country highway it once was. But it is almost comically overwhelmed by its vehicular load — those caught on Culebra as people drop off or pick up kids from nearby schools might want to find a podcast.

One of the tracts – we’ll abbreviate the official 11-digit ID and call it “821.05” – grew by 468 percent in a decade. In 2010 it had 2,194 people. Last year it had 12,469.

The other two tracts — 720.04 and 817.29 — grew 325 percent and 298 percent, respectively.

By comparison, the relatively tame growth north of Loop 1604 was in the 50 to 200 percent range. (Census wonks may protest that tract boundaries change from decade to decade, so it’s not apples to apples, but local demographers believe the comparisons are still valid.)

“That kind of population growth obviously has implications for transportation, housing, more police, more public services, and clearly a greater demand for water, with all those new yards and swimming pools,” said state demographer Lloyd Potter, who is also a professor at the University of Texas at San Antonio.

A larger and more diverse tax base, Potter acknowledges, can bolster the city’s ability to pay for such things as parks, trails and the arts. But he wonders “if people in poverty or on the edge of it” will believe they get enough benefit from the exponential growth of affluent suburbs to justify the work a city must do to accomodate it.

The lure

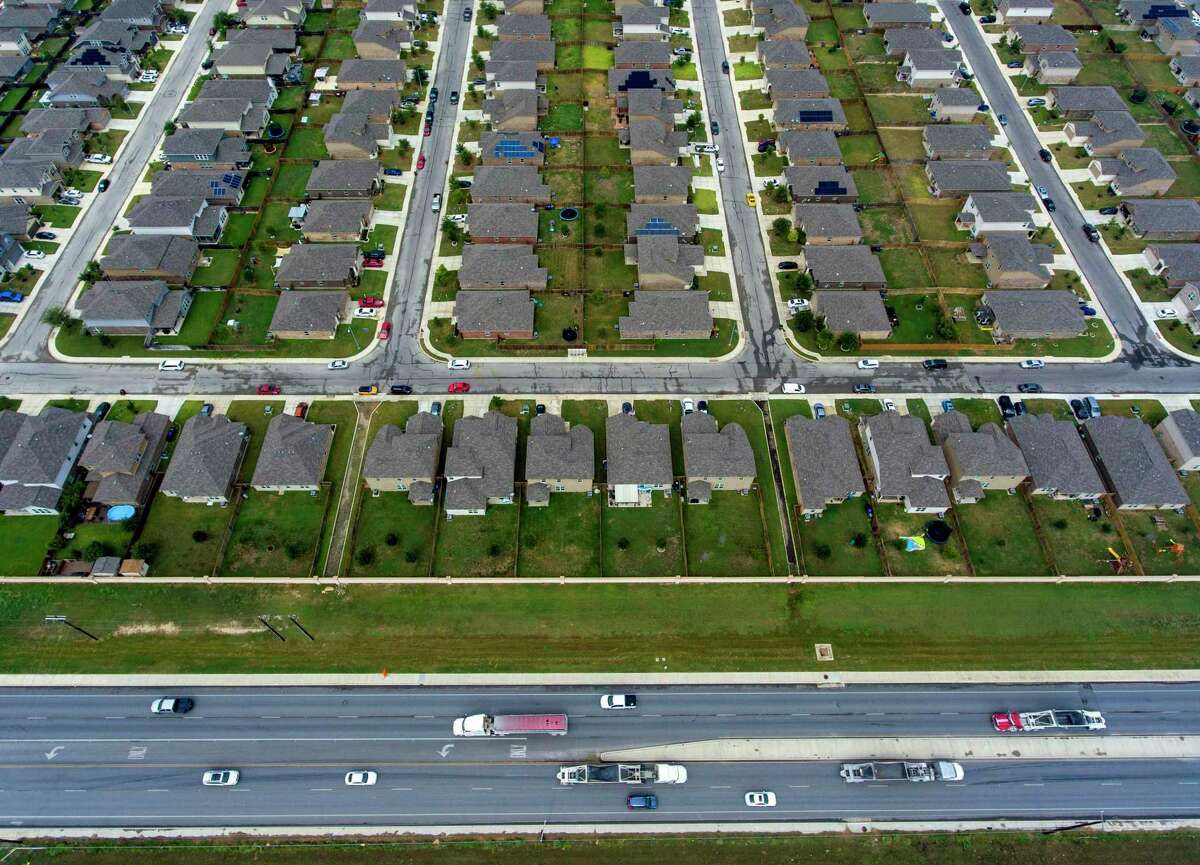

Homes on the Far West Side crowd against Culebra Road, the often-clogged traffic artery connecting the subdivision’s residents with the rest of the city. Three census tracts in the area had Bexar County’s fastest population increases from 2010 to 2020 — one of them grew 468 percent.

William Luther /Staff

“The first thing I hear from these buyers is, ‘I want to live in a safe neighborhood.’ It’s never about churches or politics,” said real estate agent Liz Petroff, adding that her most expensive homes ($500,000 to $2 million) have mainly attracted Houstonians.

The metastasizing subdivisions, many of which tout their gated security, have rustic names by which developers evoke the rugged cactus-and-cedar terrain they bulldozed to create them — Kallison Ranch, Stillwater Ranch, Redbird Ranch, Wind Gate Ranch, Riverstone, Cobblestone, Stoney Creek and various “Preserves.”

This suburban world by now is as familiar to most Texans as Friday night football. Convenient chain pharmacy or fast food locations pop up where tin-roofed sheds once stood amid golden-cheeked warbler habitat. A year or two later come two-story elementary schools and three-story high schools, catalyzing the traffic.

The Culebra corridor has been San Antonio’s No. 1 real estate “sub-market” for most of the past 15 years, said Cathy Teague, marketing director for KB Home, a national builder whose stock price has more than tripled since early 2020.

In December, the company plans to open The Preserve at Culebra, with 1,000 homes. It has other developments nearby, such as CrossCreek and Falcon Landing.

“We try to aim for the first-time buyer, but that price point has changed radically in San Antonio,” Teague said. “You used to be able to buy a very nice home for $150,000. That’s no longer available.

“I do like watching people choose their countertops and bedrooms. I see them at closing, setting down roots, and there’s a real sense of accomplishment.”

Contrary to local hyperbole, the new buyers in San Antonio aren’t all from the West Coast. Realtors suggest more than 80 percent of them come from within Texas, including a sizeable portion “moving up” from elsewhere in Bexar County.

Fun facts: Realtor.com says that in 2020, the non-Texas counties whose residents most frequently searched online for homes in San Antonio’s hottest upscale markets were Essex County, N.J. (in the New York City metro area) and DeKalb County, Ga. (Atlanta metro area).

But, true enough, the state that perennially produces the most online San Antonio searches is California.

“Some of my California clients have talked about feeling unsafe where they were, more people living on the streets, feeling unsafe for their children,” Petroff said. “But most of them are just amazed that what costs $400,000 here, costs $800,000 back home.”

Seller’s market

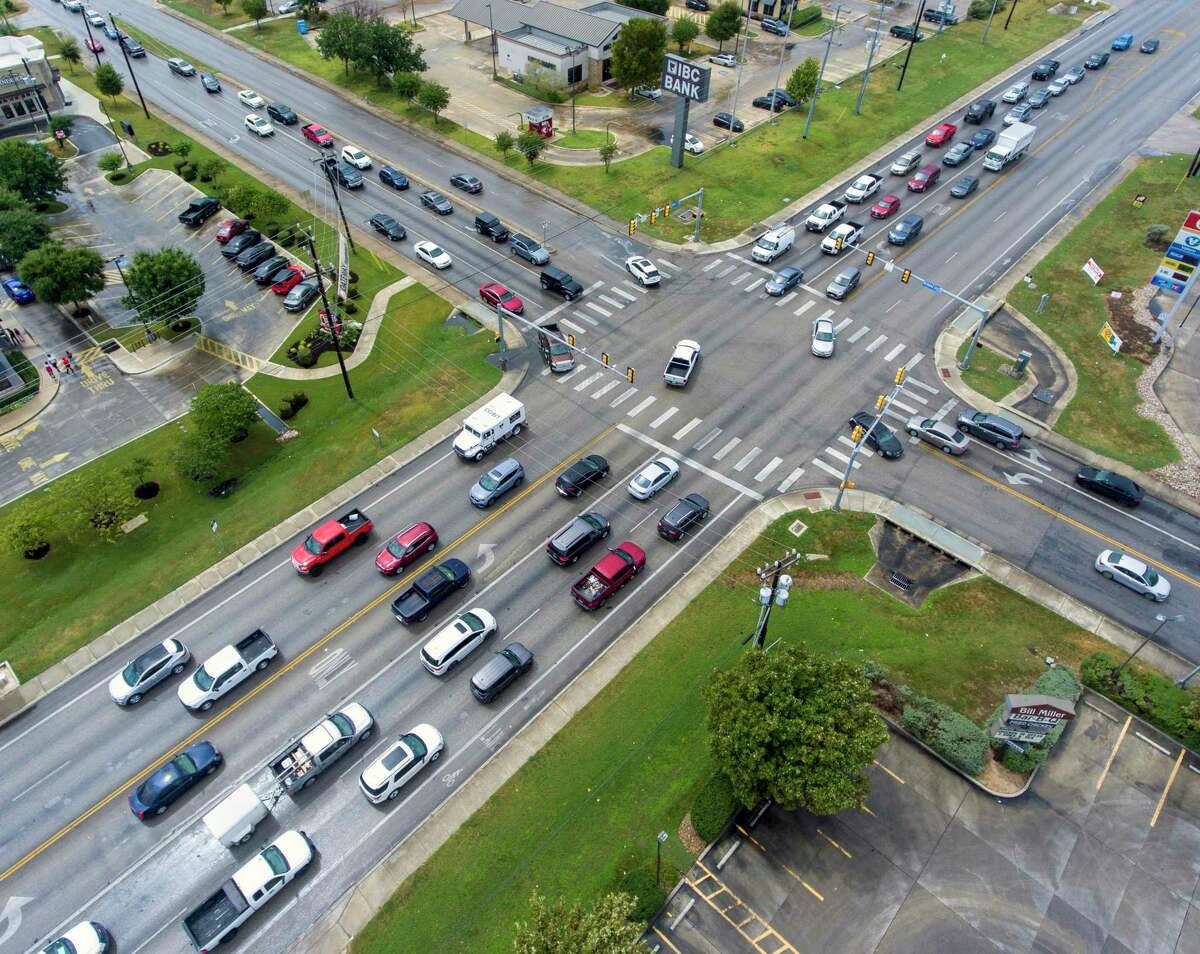

Cars navigate the traffic lights at the intersection of Culebra Road and Westwood Loop in the Far West Side beyond Loop 1604. Three census tracts in the area had Bexar County’s fastest population increases from 2010 to 2020 — one of them grew 468 percent.

William Luther /Staff

Not so strangely, perhaps, millions of those online searches for San Antonio real estate came in the middle of the coronavirus pandemic.

But demand for homes here was sizzling long before COVID-19 arrived in March 2020. So it has remained — maybe because interest rates stayed low and buyers such as retirees and military personnel weren’t tied to an uncertain job market, observers theorize.

But the pandemic did affect the supply side of things, said Laura Guerrero-Redman, an agent for the real estate brokerage firm eXp.

Inventory dropped. Soon-to-be empty-nester parents didn’t sell as planned because their kids went to college online. Elderly folks didn’t transition to nursing homes for fear of the coronavirus. Eager job seekers had to cool their jets.

Bexar County continued building houses despite a crippled supply chain — chronic delays in getting carpet, shingles and bricks made worse by national shortages of carpenters, roofers and concrete finishers.

“I’ve had people ready to close, and their new house didn’t have a stove,” Guerrero-Redman said. “Legally, you cannot close on a VA/FHA loan if you don’t have a stove.”

“We’d put in orders for shingles from five manufacturers and go with whoever got them first,” she added. “It’s exhausting, but if you don’t manage your (construction) timeline you will have lots of pissed-off clients.”

One day Guerrero-Redman was in dire need of wasp spray. Roofers, painters and even security camera installers get stung quite a bit.

“Walmart didn’t have any. At H-E-B, the shelves were empty,” she said. “Finally, I went to Home Depot and bought six cans. A manager told me builders usually come in by 8 a.m. and clean out all the shelves.”

Carol Case, a Realtor with Kuper Sotheby’s International Realty, hasn’t seen anything like this fevered San Antonio market in her 40-year career. She and her colleagues talk of homes being sold “as is” without inspections and desperate buyers offering $100,000 over the asking price.

“I saw one house that had gone from $445,000 to $598,000, and (the seller) hadn’t done anything except move some rocks,” Case said. “There’s a frenzy of people thinking they won’t ever find another house.”

Calilfornia exodus

Cars navigate the intersection of Culebra Road and Westwood Loop in the Far West Side beyond Loop 1604, where traffic is a constant complaint. Three census tracts in the area had Bexar County’s fastest population increases from 2010 to 2020 — one of them grew 468 percent.

William Luther /Staff

Mario Estrada is used to 60-to-90-minute commutes from his home in Rancho Cucamonga, Calif., about 35 miles east of his logistics management job in Los Angeles.

“That’s almost unheard of in San Antonio, I think,” said Estrada, as he plodded along L.A.’s choked Interstate 605 late one September afternoon.

At 50, he lives with his wife, Cynthia, a registered nurse, his parents and his three children, ages 2, 17 and 21. The couple was married in San Antonio 22 years ago – dozens of her relatives live here — and have been considering a return for years.

Now they have a spreadsheet to plot a move in April or May. Around the Christmas holidays, they’ll shop for homes convenient to hospital jobs, maybe older ones with some character and more yard than their current half-acre.

“San Antonio offers a big-city feel with culture you can’t get many places,” said Estrada, who came to the United States in the 1980s with his parents as refugees from war-torn Guatemala.

He already had memorized three San Antonio ZIP codes north of Loop 1604, but was intrigued by an area he described as “south of Helotes, maybe on the way to Castroville.” The Far West Side, in other words.

The Estradas feel fortunate. Both have good jobs and believe they can easily find the same in San Antonio, plus good schools for their younger kids. They hope to make a six-figure profit when they sell their $800,000 California home.

Estrada considers himself conservative politically, but the idea of fleeing California for its liberal politics is “pretty extreme,” he said.

“I try to teach my kids that we are Americans first,” he said, stalled in traffic during an L.A. sunset. “People get upset about the mask mandates out here, but it’s overblown. There are bigger fish to fry.”

The more right-leaning members of a Facebook group helpfully called “Californians Move to Texas!” seem more pushed than pulled, though.

Mary Jenkins, 53, a dental hygienist from Thousand Oaks, wrote that she and her husband are moving to San Antonio and semi-retirement because of “$4.30-a-gallon gas, being over-taxed for everything…and wanting to make our own choices.”

She, too, complained about a “dictator” governor and mocked her state’s Los Angeles-to-San Francisco high-speed rail project. But when asked why she’s coming to Texas, Jenkins mellowed. She wants to be closer to a son who is just out of the Army and expecting his first child with his San Antonio fiancée.

Real estate professionals here say “moving close to the grandkids” is a true demographic category — especially if the children live in warm weather states.

How do they vote?

Cars and trucks wait for a traffic light to change on Culebra Road in the Far West Side beyond Loop 1604. Three census tracts in the area had Bexar County’s fastest population increases from 2010 to 2020 — one of them grew 468 percent.

William Luther /Staff

About 15 years ago, retiree John Brouse moved to Wind Gate Ranch, a gated community of mid-$400,000 homes off Culebra near the future Harlan High School.

Originally from Pennsylvania, he worked in naval aviation, fiber optic technology and the financial sector. His wife, Suzanne, has roots in San Antonio. Moving around a lot when he was in the Navy, they often visited to see relatives and dream about one day living in the tranquil hills west of the city.

“We wanted big open lots,” said Brouse, 72. “And no privacy fences. We found with fences people didn’t get to know their neighbors as much.”

Brouse described his subdivision as “a pretty mixed community.”

“Lots of interracial marriages. Older folks,” he said. “Lots of ex-military and civil servants. Primarily Christian. A number of Hispanics. Politically, maybe 20 percent Trumpers, 20 percent Democrats. The rest, I have no clue.”

Republican political strategist Kelton Morgan has a clue. He’s a maven of direct mail politics and knows San Antonio’s voting precincts — the seven that correspond to the three booming census tracts are still “nominally Republican,” he says, but a year ago, after voting 65 percent for Republican governors in previous races, the tracts went 52.5 percent for Democrat Joe Biden for president.

“Like a lot of the country, those tracts favored Republicans locally, but had had enough of the Trump clown show at the top,” Morgan said.

In the 2022 mid-term elections, Morgan expects voters on the Far West Side will be thinking about crime, traffic and (always) the economy, and that “persuadable white suburban women” will continue to be the swing voters.

“Bill Clinton called them soccer moms in 1992,” he said. “You must have them to win. Not much has changed in 30 years.”

Morgan remains fascinated with people who “just picked up and left everything they knew to come to San Antonio.”

“And what they found in this 65 percent Hispanic town is some remarkable diversity,” he added. “Hindu temples. Mosques. A powerful Asian chamber of commerce.”

As with many newly-populated suburban areas nationwide, Bexar County’s three fastest-growing census tracts are racially diverse. The residents and the real estate people who sold them homes credit an emerging middle class of ethnic minorities and the presence of Joint Base San Antonio-Lackland less than 20 miles away.

The new melting pot

In Census Tract 821.05, the Black population grew 1,350 percent in 10 years (from 85 to 1,233). Hispanics now make up almost half of the tract’s population, having grown 714 percent to outnumber the “white alone” category by roughly 2,000 people.

In tract 720.04, the numbers of Blacks and Hispanics both increased by more than 400 percent, twice the pace of the white expansion. The picture is much the same in Tract 817.29. In the three tracts, Asians grew 1,200 percent, 445 percent and 856 percent, respectively.

Rob Hester, a real estate agent who works in the area, says nearly all of his clients are active or retired military, including plenty of young first-time buyers, most earning under $80,000 a year and hoping to keep their commute to JBSA-Lackland under control.

“They all accept suburban sprawl,” Hester said. “But very few want to be outside of that 35-40 minute range.”

The real estate market of the past eight years has been remarkably good to many of his clients. After living here just two or three years, he says, some relatively young home-sellers made profits of $40,000 to $80,000 when they transferred to their next post. Others rent out their houses using an extensive, informal, internet-driven network of military referrals.

A growing number of out-of-state San Antonio buyers now find their homes on YouTube through agents like Greg Foster, who lives near Alamo Ranch, has daughters at Harlan High and in middle school, and often pitches the Far West Side on a fast-paced internet show that feels part infomercial, part morning TV talk show.

Foster, who is Black, says he is often asked very directly by Black out-of-state clients about diversity and cultural awareness in the area.

“I have to be very delicate about this because of our Realtors code,” he said. “But I tell people, me and my family have felt welcomed and completely comfortable out here. Because it’s so affordable, we get everyone from everywhere. It’s a melting pot.”

On his videos, Foster covers everything from shopping to overcrowding at the schools to traffic he describes as “worse than ever.”

“I think the city has trouble keeping up with the infrastructure,” he said. “They widened Culebra, and that was great for a while, but they need to widen it from Ranch View all the way to Harlan. It’s terrible right now.”

Nearly everyone agrees, even John Brouse, the optimistic Wind Gate Ranch resident.

“We knew we’d see modest growth, but in our wildest dreams we never thought we’d see this amount,” Brouse said. “We thought we’d be living in the country for years.”

‘An explosion’

John Dieltz and his wife, Carla, moved to Wind Gate Ranch in 2013 from Comal County specifically because their commute time on U.S. 281 in and out of San Antonio had doubled in a few years from traffic and a string of new traffic lights. Now they’re going through it again.

“We thought it would be more gradual,” said Dieltz, a retired Air Force major. “It’s been more like an explosion. There used to be some country out here. Not anymore.”

Dieltz said the Alamo Ranch shopping area at Loop 1604 and Culebra is “a really nice area, but I will simply not go there on weekends. I’ll drive miles to avoid it.”

Echoing the feelings of others, Dieltz says the traffic has been made worse by Northside Independent School District’s practice of clustering its schools, rather than dispersing them more evenly.

The district’s spokesman, Barry Perez, said the traffic problem around many of the new campuses “is the pain of growth” and that district officials try to mitigate it, even down to the micro-level of asking road crews to alter the cycle of a traffic light.

“But we try never to ask them to delay a project, because the finished product usually improves things,” he said.

The Alamo Ranch traffic simply cannot be fixed, said Jamie Bierschbach, a real estate manager with Quik Trip convenience stores who analyzes a lot of San Antonio traffic patterns before he locates a new store. He moved to Kallison Ranch in 2016 with his wife, Karen.

“You can’t change that area now,” Bierschbach said. “The highways were poorly designed. It just evolved over time.”

Would more mass transit help?

“We’re in Texas,” Bierschbach observed. “Mass transit will never be a solution. People like their trucks. (We need) better roads, better timed lights.”

The seeming inevitability of suburban sprawl and the demise of the natural landscape is the daily mental wallpaper for urban thinkers such as Rick Cole, director of the Washington, D.C.-based Congress for the New Urbanism.

Cole, a former California mayor and city manager, says he has had “a soft spot for San Antonio” after attending a conference here in the 1980s and talking with the former, current and future mayors Lila Cockrell, Henry Cisneros and Nelson Wolff.

People say freedom is all about living anywhere you want, but “the typical suburban housing tract, with strip shopping and an office park,” though it might be “relatively safe and relatively cheap,” does not hold its value well, Cole said.

“This is one of the thorniest challenges in America,” he said. “They’ll wear out in about 30 years.”

For now, harried suburbanites “waiting in lines of 27 cars to pick up their kids from school” are resilient and will “find community and do everything they can to make unpromising landscapes workable,” Cole said. “And that’s to be applauded. But they’re rowing against the tide.”

bselcraig@express-news.net