9/11 hijackers were ‘hiding in plain sight’ before the 2001 attacks. How did they do it? – USA TODAY

On a quiet Tuesday in June 2001, two men walked into a store in a busy strip mall in Fort Lee, New Jersey, that rented mail boxes for people on the move who needed a temporary address to receive checks, bills or personal letters.

A mile away, the usual steady stream of cars and trucks swept across the George Washington Bridge that spanned the Hudson River. A dozen miles down the Hudson, at the tip of Manhattan, the World Trade Center’s twin towers poked the sky.

At Mail Boxes Etc., a now defunct storefront in Fort Lee, New Jersey, the men plunked down an indeterminate amount of cash and were assigned Box 417. FBI agents later learned they told a clerk they represented a firm based in Paterson, New Jersey, and explained they needed the temporary mailbox only until late September.

Actually, the men, Hani Hanjour and Nawaf al-Hazmi, didn’t need the mail drop that long. And their explanation was just a ruse.

The photo of a grieving 9/11 son was unforgettable:20 years on, he recalls his mom’s sacrifice

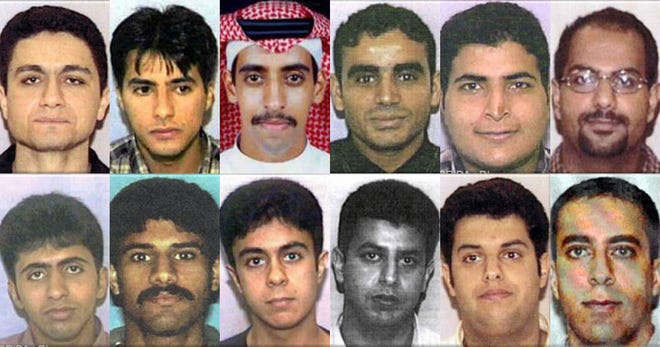

On Sept. 11, 2001, Hanjour and al-Hazmi joined 17 other followers of Osama bin Laden’s al-Qaida network in hijacking four commercial jetliners and crashing them into the trade center’s twin towers, the Pentagon in northern Virginia and a farm field in Shanksville, Pennsylvania. Al-Hazmi helped subdue passengers aboard American Airlines Flight 77, which hit the west wall of the Pentagon. Hanjour piloted the plane.

Their rental of a temporary mailbox in New Jersey represents just one of thousands of examples of seemingly ordinary movements by the 9/11 killers in the months leading up to the attacks. These details were chronicled in an exhaustive and now-declassified FBI report that was reviewed by the USA TODAY Network as America commemorates the 20th anniversary of the 9/11 attacks.

In grim yet mundane detail — assembled from all manner of electronic records and old fashioned gum-shoe police work — the report, titled “Hijackers Timeline,” offers a day-by-day portrait of the 19 al-Qaida operatives before they set off on their suicide-murder mission that killed nearly 3,000 people and set America’s longest war in motion.

Living mostly in central Florida, Southern California, northern Virginia and northern New Jersey, they rented cars, opened bank accounts, navigated complicated city streets and highway exit ramps, rented motel rooms, dialed each from pay phones in hair stylists and hardware stores, ordered meals in diners, took flying lessons, played video games, lifted barbells at gyms and even purchased sun glasses at a Macy’s department store.

20 years later:How a vision for the 9/11 Memorial blossomed into a piece of New York’s everyday fabric

Their time in northern New Jersey is especially illuminating. The crowded, multicultural hamlets of Bergen and Passaic counties became a meeting ground for nearly a dozen of the 19 terrorists during the summer of 2001. And the connection to northern New Jersey also gave rise to unfair accusations that some members of the region’s Muslim community may have knowingly assisted them.

Some, like the 9/11 plot’s ringleader, Mohamed Atta, flew in from Florida, checking into a motel in Wayne for a few days and then leaving — and then returning days later. Others, such as Hanjour and al-Hazmi, bounced between motels and an apartment in a two-story home in Paterson at the same address Hanjour cited as a business office when he rented the mail drop.

The day after renting the mail box, Hanjour withdrew $161 from an ATM machine at a bank across the street from Holy Sepulchre Cemetery in Totowa, New Jersey.

Hanjour could not possibly know at the time that just two months later, Holy Sepulchre would become the final resting place of the first official victim of the 9/11 attacks, the Rev. Mychal Judge, the Catholic chaplain of New York City’s fire department.

Judge perished while ministering to fire fighters at the World Trade Center’s North Tower. The photo of first responders carrying his body from the rubble has become an iconic symbol of the pain of that day.

The close proximity of the ATM and Judge’s grave, which is now an unofficial 9/11 shrine, illustrates how closely intertwined the terror plot was with its tragic aftermath. At the same time, the hijackers’ comings and goings in northern New Jersey offer a glimpse of how they openly took advantage of American life and its open society — before attacking America in a way that challenged that openness and raised questions about how the U.S. might better surveil its citizens.

How did they do it?

But examining that story now, as America commemorates the 20th anniversary of the 9/11 attacks, reignites one of the most persistent and controversial mysteries of that tragic day: How did 19 men from the Middle East — most of whom barely spoke English — manage to pull off such a deadly mission without being detected?

Hanjour and al-Hazmi were especially active.

The day before renting the mailbox in Fort Lee, they worked out at a Gold’s Gym in Totowa, New Jersey. Hanjour also rented planes at Teterboro and Essex County airports to practice flying. In one case, he made a pass over the Hudson River and the World Trade Center. Al-Hazmi regularly rented cars at a Jeep dealership in Wayne.

Neither Hanjour nor al-Hazmi — nor any of the other hijackers — resorted to using fake names. Nor did they live underground and avoid contact with ordinary Americans.

“They were essentially hiding in plain sight,” said John J. Farmer Jr., the former New Jersey attorney general and senior counsel for the 9/11 Commission who now directs the Rutgers Eagleton Institute on Politics. “They were simply melting into the general population the way the planes they hijacked melted into the radar or ordinary air traffic.”

Also, none of the 19 hijackers arrived in the U.S. without documentation. They arrived on commercial jetliners with ordinary — and entirely legal — visas.

America’s elaborate and expensive security services ignored warnings during the summer of 2001 that al-Qaida wanted to attack America — and, in fact, were dispatching terrorists to U.S. soil.

Two of the hijackers — al-Hazmi and Khalid al-Mihdhar — were known to the CIA as al-Qaida operatives. The CIA even tracked al-Hazmi and al-Mihdhar from the Middle East to Malaysia to Thailand and then to Los Angeles. There, though, the CIA, which is prohibited from spying inside the U.S., gave up the trail. And the CIA never shared al-Hazmi and al-Mihdhar’s movements with the FBI, which conducts counter-terror investigations in America.

The botched hand-off by the CIA to the FBI is considered one of the most embarrassing security failures in U.S. history. It is now a centerpiece of a massive federal lawsuit by thousands of relatives of 9/11 victims who claim that Saudi Arabian officials helped the hijackers inside the U.S.

Afghanistan:White House asks Congress for billions in emergency funds for Afghan resettlement

The failure to stop al-Hazmi and al-Mihdhar is also the source of two decades of anguish for Mark Rossini, a former FBI special agent and counter-terror specialist who was part of a team monitoring bin Laden’s al-Qaida network in the months leading up to 9/11.

During the summer of 2001, Rossini was assigned as a FBI liaison to the CIA’s bin Laden squad, code-named “Alec Station,” at the spy agency’s headquarters in Langley, Virginia. Working with the CIA, Rossini learned about the arrival of al-Hazmi and al-Mihdhar as early as 2000. He pleaded with the CIA to pass on the information to his FBI colleagues across the Potomac River in Washington, D.C.

But Rossini was told to keep quiet. The CIA considered the information top secret — not ready for the FBI. Rossini said that he was told that if he broke protocol and told the FBI, he would charged with a federal crime.

Today, Rossini, 60, divides his time between France and Spain. He left the FBI in 2008 after he broke rules to examine records in an unrelated case without permission.

He wishes he broke the rules in 2001 with the CIA.

“It’s not even frustrating. It’s debilitating,” Rossini said in a phone interview from Spain with the USA TODAY Network. “It basically almost caused me to have a nervous breakdown. It drove me to the brink. I felt like Don Quixote fighting windmills. I lost my faith in justice. I lost my faith in the system. I don’t really understand it anymore.”

Rossini said his CIA colleagues told him the arrival of al-Mihdhar and al-Hazmi was not a sign of an attack on America but a diversion. Rossini said the CIA believed — mistakenly — that the next al-Qaida attack would take place in South East Asia, Rossini said. Now Rossini believes the CIA thought it might use al-Mihdhar and al-Hazmi in an ill-conceived plan to infiltrate al-Qaeda.

“ ‘This is CIA information and you are not to tell the FBI,’ ” Rossini said he was told. “I remember it like it was yesterday.”

A few weeks before the 9/11 attacks, the CIA finally relented and notified the FBI that at least two al-Qaida terrorists — al-Hazmi and al-Mihdhar — were on the loose inside America. But it was too late.

“If the FBI was told earlier, the plot could have been stopped,” Rossini says. “No doubt in my mind.”

After 20 years, the CIA has still not explained why it did not pass the information on al-Hazmi and al-Mihdhar to the FBI.

Peter Bergen, a best-selling author of several books on bin Laden and a CNN security analyst, said he has come to believe that the CIA did not willfully ignore the growing threat of al-Qaida.

“I think it’s incompetence,” Bergen said, explaining why the CIA did not sound the alarm on al-Hazmi’s and al-Mihdhar’s arrival in the U.S. “Incompetence is sometimes a better explanation of human activity.”

Opinion:We treat COVID patients. Here’s why the ‘pandemic of the unvaccinated’ narrative is wrong.

Did they have help?

In northern New Jersey, al-Hazmi and al-Mihdhar settled in nicely — as if they seemed to know their way around.

In mid-July, al-Mihdhar, accompanied by al-Hazmi’s brother, Salem, and another hijacker, Abdulaziz al-Omari, rented a mailbox at a storefront in Paterson.

Salem al-Hazmi would join his brother aboard the jetliner that crashed into the western façade of the Pentagon. Al-Omari was part of the hijacking team that took over American Airlines Flight 11, which left Boston and crashed into the World Trade Center’s North Tower.

It’s not entirely clear why the group of hijackers needed another mailbox. The FBI timeline investigation was not able to determine that.

But, once again, the mailbox rental touched on the mystery of how the hijackers went about seemingly normal activities without arousing any suspicions. It also raised the question of whether anyone helped the hijackers.

Mary Galligan, a former FBI supervisory agent who directed the bureau’s on-scene investigation of the al-Qaida bombing of the U.S.S. Cole in Yemen in 2000 and went on to lead the post-9/11 tracking of the hijackers that was known as the “Pentbomb” investigation, points out that the hijackers “didn’t commit any criminal acts” until the day they hijacked the jetliners. As a result, she said, the hijackers did not catch the attention of police — or private citizens.

“The first criminal act they committed was taking over the planes,” said Galligan, who retired from the FBI in 2013 and now directs cybersecurity for a large consulting firm based in New York City.

One question Galligan’s agents were not able to resolve, she said, was whether U.S. citizens actively participated in the plot by knowingly assisting the hijackers.

Like Tom Kean, the former New Jersey governor who chaired the 9/11 Commission, Galligan has come to believe that U.S. citizens likely helped the hijackers with advice on ATM machines, banking, phone service and other seemingly routine activities without knowing they were involved with dangerous terrorists.

“I think that any help they got was from people who did not know they were hijackers who were going to commit a terrorist attack on 9/11,” Galligan said.

As a result, police made few arrests of potential collaborators.

The one exception involves Mohamed el-Atriss, an Egyptian-born storeowner in Paterson who sold fake IDs.

For years, el-Atriss sold the phony IDs openly, mostly to undocumented immigrants from Latin America and Mexico. But just before the 9/11 attacks, he sold IDs to al-Mihdhar and al-Omari.

After the 9/11 attacks, the FBI contacted el-Atriss but did not arrest him. At the same time, however, local police in Paterson were also tracking el-Atriss and arrested him in 2002, charging him with a series of state crimes for selling false documents.

Federal authorities, claiming the need to preserve national security secrets, quickly shut down the case, sealing all documents and testimony.

El-Atriss, who spent six months in the Passaic County Jail, has long claimed that he had no idea that al-Mihdhar and al-Omari were anything more than another ordinary customers in search of ID cards that seemed to meet the approval of many local cops. El-Atriss eventually pleaded guilty to lesser charges and was sentenced to five years probation and dealt a $15,000 fine.

A naturalized U.S. citizen, el-Atriss continually insisted that he was not part of the 9/11 plot and openly condemned the attacks. But he felt he had been unfairly branded as a conspirator because of his unintended connection with the hijackers.

He has since moved from Passaic County, New Jersey, and could not be reached for comment. But in 2006, he told NorthJersey.com: “Your country is my country and my children’s country. I am an American citizen. When I took the oath, I meant every word of it. Unfortunately, I am the person who handed an ID to a hijacker.”

Two decades later, the Passaic County detective who led the local investigation of el-Atriss, believes that el-Atriss knew they were “bad guys.”

“He knew they weren’t there as tourists to see the Statue of Liberty,” said Fred Ernst, a sergeant in the Passaic County Sheriff’s Department when he investigated el-Atriss.

Now 70, Ernst said he would like to re-open the case.

“He may not have known they were going to hijack planes,” Ernst said of el-Atriss. “But there is no question in my mind that he knew these guys were bad guys.”

The el-Atriss episode — and its divergent story lines and theories — underscores how unsettled the story of the 9/11 hijackers remains.

Another disturbing episode in New Jersey took place on a night in July 2001 at a cheap motel.

South Hackensack Police Officer David Agar, then 25, pulled into the parking lot of the Congress Inn as part of a routine patrol. Agar, now 45, and a lieutenant with the Bergen County Prosecutors Office where he oversees intelligence and counter-terror investigations, was looking for suspicious activity.

Back then, motels in that area were frequent scenes of drug deals and prostitution.

Agar spotted a light blue Toyota Corolla with California plates.

“To me, the vehicle stood out,” Agar said in a recent interview. “We didn’t get that many cars with California license plates in South Hackensack.”

He stopped and wrote down the plate number. Then, he punched the number into a national computer crime index that was monitored by the FBI and contains information on outstanding warrants and other warning signals that might alert local police officers to make an arrest or summon federal investigators.

The license plate turned out to be a rental car. The renter: Nawaf al-Hazmi.

But the FBI had not yet been told by the CIA that al-Hazmi was an al-Qaeda operative. The check of the FBI’s computer offered no warning that al-Hazmi was anything more than just another guy with a rental car.

If it had, Agar is confident that he would have summoned other police and possibly the FBI to confront al-Hazmi — and his friend that night in Room 506 at the Congress Inn, Khalid al-Mihdhar.

But without any warning or instruction to arrest al-Hazmi, Agar had no choice but to drive on and continue his patrol in other parts of South Hackensack. His brief brush with the 9/11 story lasted all of 30 seconds, he said.

Today, the story is not just a reminder of how the hijackers blended in so intimately into American life. It’s also a reminder of just how close police came to possibly stopping the 9/11 attacks.

“Looking back, I don’t know if we could have stopped all the hijackings,” Agar said. “In my mind, maybe we could have saved some lives.”

Follow Mike Kelly of NorthJersey.com on Twitter: @mikekellycolumn